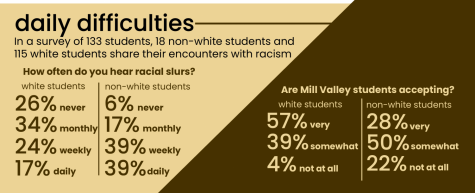

Students and administration face racist language within the classroom

Minority students continue to be impacted by the prevalence of racist slurs at school despite current consequences

Racial slurs and derogatory remarks have a long-lasting impact on people of all races and ethnicities and can lead to increased tension within society.

February 17, 2020

While sitting through another day of AV Production Fundamentals last year, junior Beth Desta got into a heated argument with a boy sitting next to her in class.

Desta doesn’t remember what instigated the conflict. What she does vividly recall, though, is the boy’s response.

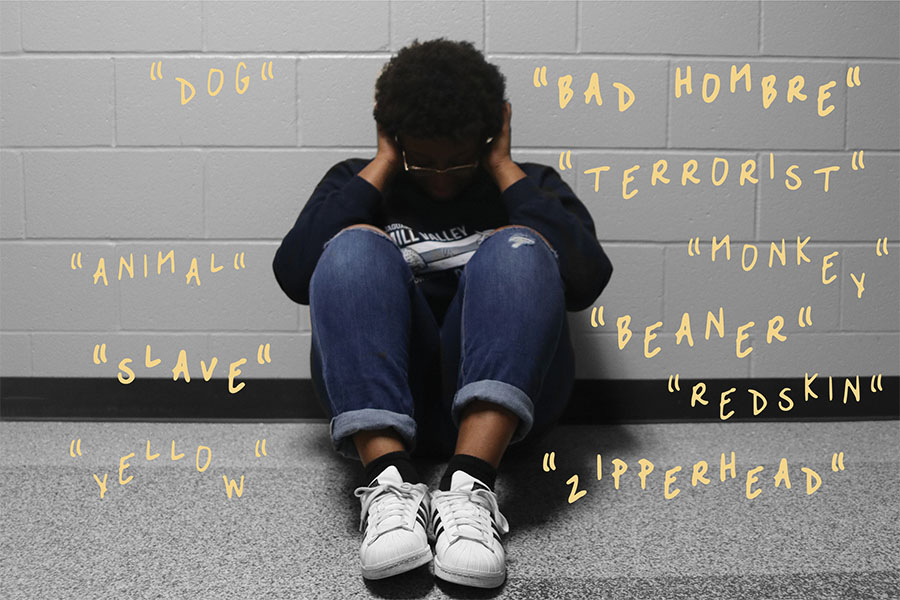

“He disagreed with me. He just looked at me in the eyes and called me the n-word,” Desta said.

According to Desta, the use of racial slurs, including the n-word, is commonplace at Mill Valley. In her experience, white students callously use the word while joking with their friends or singing along to popular songs, while they lack an understanding of the deep racist roots of the word — or meaningful consequences for its usage at school.

While Desta described principal Tobie Waldeck as extremely upset about the incident, the student who called her the n-word to her face received two days’ in-school suspension, which proved to her that “the administration doesn’t really care.”

Sophomore Ryan Lucas shares Desta’s disappointment in the school’s response to the use of racist slurs at school. After a student in Lucas’s World History class called her the n-word and Lucas reported it, the student received a three-hour detention. To Lucas, the punishment was woefully inadequate.

“With all the history of that word, with slavery and Jim Crow and all of that, it should have been a lot more than just a three-hour detention,” Lucas said.

Desta shares her disappointment regarding the inconsistency and lack of severity in the school’s punishments for racial slurs, referencing a black student who received two days of out-of-school suspension. Desta’s harasser received only one day of out-of-school suspension, and Lucas’s received zero days of out-of-school suspension.

“I just don’t think they handle it seriously enough when it comes to non-black people saying the n-word. A black kid got suspended for even longer for saying it,” Desta said.

Assistant superintendent Alvie Cater disagrees with Desta’s assertions of unfairness and believes that the district already strongly opposes racial harassment at school.

“USD 232 will not tolerate racial slurs in our schools, on school property, or at school-sponsored activities. We want all schools to be safe places for each student so they can focus on learning and doing their very best,” Cater said. “Students have enough to do without having to worry about insensitive and inappropriate behavior on the part of others.”

Cater notes that the consequences for using racial slurs are determined by the principal based on “the student’s age and maturity, the nature and seriousness of the infraction, the student’s previous disciplinary record, and any other relevant factors.” He also explains that consequences for the use of racial slurs can range from a detention to a long-term suspension.

While the claim that white students who use racial slurs are punished too lightly is disputed, the harm the slurs cause to minority students cannot be understated. After she was racially harassed, Desta wanted to transfer.

“After that, my mindset was, ‘Mill Valley is racist. Mill Valley is racist. Everyone here sucks,’” Desta said. Even when Desta isn’t individually attacked at school, the atmosphere of rampant racist language and attitudes hurts her.

Even when Desta isn’t individually attacked at school, the atmosphere of rampant racist language and attitudes hurts her.

“I come back from school in a bad mood most days. There are some days where I come to school in a good mood, and I also leave in a good mood,” Desta said. “There are other times where it’s like, even if no one’s saying anything to me, or to anyone, in a derogatory way, it still kind of hits. It’s still like, ‘Okay, this is the school I go to where people don’t know or understand their limits.’”

Lucas believes that despite the prevalence of racist language at Mill Valley, the school hasn’t taken enough steps to raise awareness about the issue; to her, that’s something that needs to change.

“There definitely needs to be some type of awareness. It should be common knowledge not to use the n-word,” Lucas said, “I don’t understand why it’s not, especially with all the history behind it.”

Desta agrees; in fact, she blames the school’s failure to raise awareness for the rise of racist language.

“People just say it to say it at this point. Whether it’s in a song, or just saying it to their friends, or saying it as an insult to either another white kid or another minority student,” Desta said. “People just don’t really think about or understand what it means because the school doesn’t do anything to show them that.”

Cater does agree that more progress always needs to be made in creating a more inclusive school community.

“We believe that USD 232 must continue addressing diversity and inclusion to support the best possible learning environment,” Cater said.

Desta thinks that what’s taught in classrooms is part of the problem. She says that a friend of hers from the Kansas City school district, which is 11% white, receives much more education about non-white people and cultures; this proves to her that a diverse curriculum is possible.

“The administration needs to do a better job of teaching kids what needs to be taught, and not just what they think should be taught,” Desta said. “We learn about Christopher Columbus, but we don’t learn about Malcolm X. I think that’s one of the biggest problems here.”

While Kansas’s high school U.S. History curriculum includes Malcolm X and the Black Panther Party in its standards, a teacher said that the activist is only mentioned “peripherally” in their class. Within the department, the level of education on black history varies; a student in Aaron Cox’s U.S. History class said they learned about Malcolm X, while a student in Michael Bennett’s U.S. History class said the name didn’t come up.

Use of racial slurs like the n-word is common in popular culture as well, especially the music industry. Desta believes that, while rappers like Tupac used the n-word powerfully to refer to their black brothers and sisters, modern musicians don’t treat the word with the same respect.

“When [Tupac] was using it, it wasn’t the way that like Migos would use it now,” Desta said. “They make it seem like just like any other curse word out there, because they themselves don’t understand it.”

Another avenue for racist language to work its way into pop culture is through the popular video publishing app TikTok. Famous TikTok user Mattia Polibio recently faced backlash from fans for using the n-word in their videos, and Lucas sees racism constantly on the app.

“I spend a majority of my social media time on TikTok,” Lucas said. “There’s always going to be at least one video that I find on my page that’s blatantly racist.”

Other social media platforms like Instagram are, according to Desta, also hotbeds for racist language.

“People don’t really care about what they say when it’s over a screen. They’ll say the n-word over DM on Instagram but then never talk about in person. They’ll say, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m so sorry. I didn’t mean it,’ or they’ll try and ignore it completely.”

Desta described an online incident where someone responded to one of her Instagram posts with a direct message calling her the n-word. The person then repeatedly commented the slur below her post, then sent her another derogatory direct message.

Lucas has had a similar experience with the prevalence of online racial slurs.

“On the Internet, and even on Snapchat or Instagram, I’ll be scrolling through somebody’s story and somebody who’s white will use the n-word,” Lucas said.

Lucas and some of her black friends attempted to raise awareness about online use of slurs. They all shared a post asking white people not to use the n-word in person or online. However, Lucas didn’t think the posts had any impact.

“We’ve tried [asking people to stop],” Lucas said. “Apparently, it doesn’t work. People are going to do what they want to do.”

The frequency with which Desta sees white people using the n-word upsets her, and she believes other people of color feel the same way.

“It feels to most minorities that the white people have everything. The n-word is just one thing that they can’t have, and they can’t live without it,” Desta said. “There’s no one that says that word more than most white people do.”

Gerry Bhandal • Feb 17, 2020 at 7:59 pm

Seems like mill valley hasn’t changed one bit since I graduated!